written by Gaëlle POYADE for the 2024 edition

Pūpū from Rangiroa : treasures from the motu

Found on many atolls, including Anaa, Niau and Vahitahi, the pūpū is widely collected in Rangiroa. This mollusc is given special attention because it stands out from its maritime counterparts living in the depths of the lagoon or languishing on the sand of the beaches.

You won’t find the pūpū at the water’s edge because it usually hides underground. More precisely, in the bowels of the coral soil of the motus, “in the islets”. Passionate about shells to which he built the Motu Treasures museum in Huahine, Frank De Cagny gives us some information about the deposits. “It seems to me that it is during storms, the swell stirring up the sand so much, that the gastropods are thrown onto the shore. Thus stranded, they clump together as much on the sand as on the earth and end up buried.”

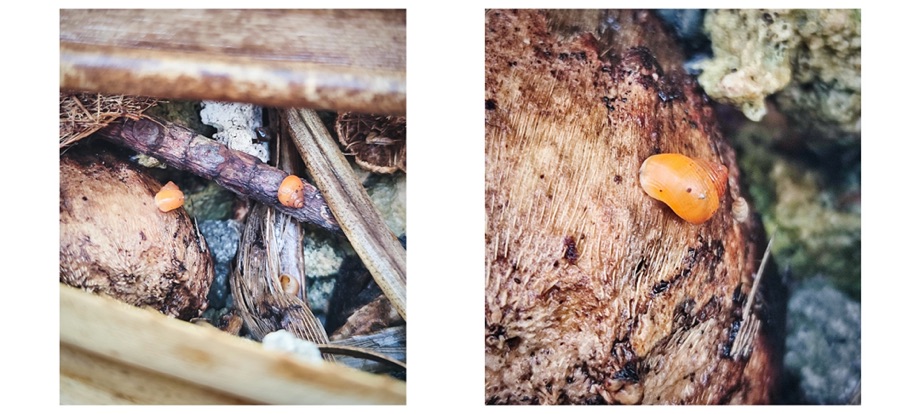

It is perhaps because of their very small size, barely 1cm, which makes them so difficult to spot, that this method of terrestrial collection prevails over aquatic and night extraction knowing that the vast majority of shellfish have a nocturnal life. In any case, picking pūpū is not easy!

The collectors, whose job is to collect many specimens for artisan jewelers throughout Polynesia, must first locate deposits situated between 30cm and up to 2 meters deep. The work involves forcefully digging into the stony substrate of the coral ring in order to uncover the shells. “We use small rakes or garden hoes,” reports Valentine Cheng, who remembers looking for them with her mother when she was a child. “With bare hands, we would really damage our fingers because the ground is so hard.”

This is followed by patient sorting using increasingly fine sieves. At this stage, the pūpū is unrecognizable, as dirty and brown as any pebble. Once washed in the sea, then bleached, it reveals its color: yellow, orange, creamy white and even red for some of them. “When the box of punu pua’atoro is full, the day is good!” exclaims the craftswoman Tehea Pambrun, who regularly stays in Rangiroa to fill her workshop with jewelry made from the precious littorines.

The work is not over, however; the tiny coral fragments that escaped the final sieving still need to be removed one by one by hand in order to make perfectly pure bags. This backbreaking work, carried out mostly squatting and under the heat of the sun, is paid in the order of 1200xpf to 2400xpf per kilo depending on the degree of cleanliness of the bags.

Finally, the pūpū is found threaded into an extraordinary array of artistic creations. It is found in garlands inside homes, in lights in churches, in festoons above tombs or even associated with other shells in the eclectic craft of jewelry. If its place goes, nowadays, from decoration to adornment, it remains above all a symbol of welcome as a traditional element of the departure and arrival necklaces in Rangiroa. This is attested by the double meaning of the word which also means “to present, to offer, to give”, as indicated by the Tahitian Academy – Te Fare Vāna’a.